“Many of our ideas come from going out, sitting at a bar, and having a drink together,” says Michael Elmgreen, the older and more talkative half of the artist duo Elmgreen & Dragset. “We actually did it just last night.” So, how many drinks does it take? “The good ideas come after one,” says the other half, Ingar Dragset, laughing. They are sitting by a well-stocked bookcase in their Berlin studio, a vast, light-flooded former water-pumping station in the Neukölln district filled with busy assistants and projects in various stages of realization. “And the ideas that are really good, the ones you see, come after five!”

The pair met 30 years ago in a nightclub called After Dark, in Copenhagen, Denmark, drawn together by the fact that they were the only two men in the venue wearing post-punk haircuts and Dr. Martens boots. Neither was a trained artist; both were on the fringes of mid-1990s Copenhagen’s thriving, defiantly noncommercial experimental scene. Elmgreen, who is Danish, was a poet frustrated by the solitary nature of the writing process. Dragset, eight years his junior and Norwegian, was involved in theater. They realized that they both lived in the same building, and went home together.

Over the decades, whether alcohol-fueled or not, many of their ideas have come to glorious fruition, combining sculpture, architecture, and site-specific theater to express a slyly political, sometimes comical, and distinctly queer point of view. Elmgreen, 63, and Dragset, 55, have a flair for turning existing structures into environments that are at once subversive and surprising. One early success was a diving board that they installed to poke out of a window at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, in Denmark, in 1997—a motif that they are reprising for their latest exhibition, called “L’Addition,” opening this month at the Musée d’Orsay, in Paris.

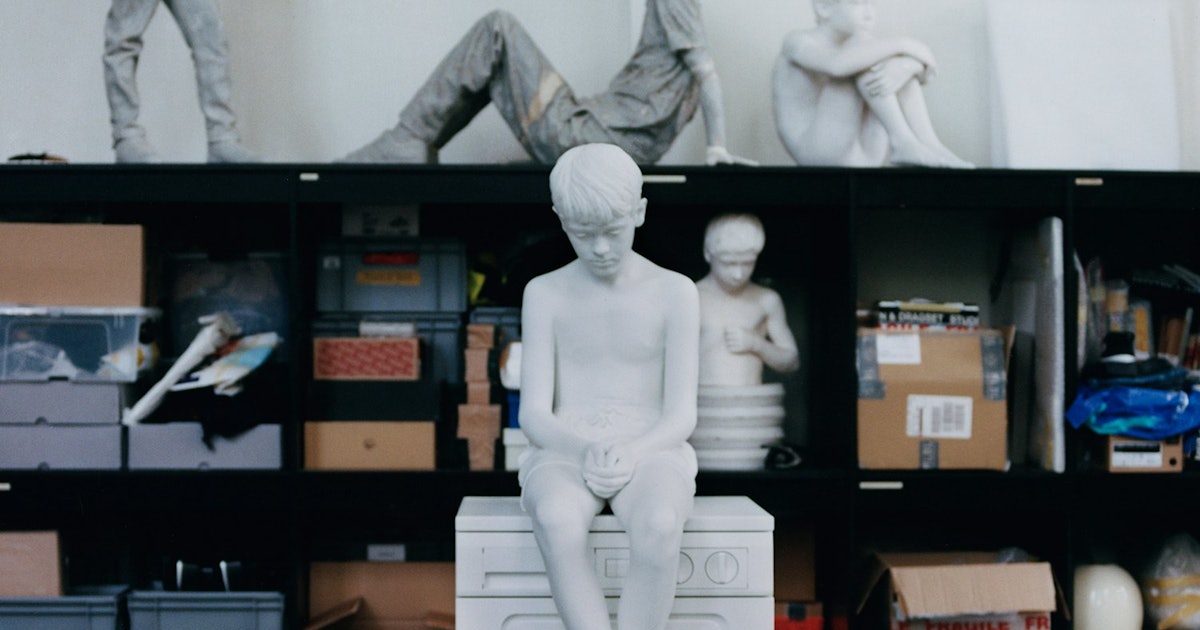

This Is How We Play Together, Fig. 3, 2023 (left), and This Is How We Play Together, 2024.

Photographed by Charlie Gates

The new board is similar to the ones they made in the ’90s, but this time it has a pensive youth standing on it. All their sculptures in the show, of men and boys, will be positioned in and around the museum’s sculpture nave, commenting obliquely on the classics from its collection. “Instead of someone washing their feet by the river, we have a boy sitting on a washing machine,” says Dragset. “We have a boy with a drone, which refers to a sculpture in the collection”—Eugène Guillaume’s Anacréon—“where a man sends off a bird from his hand.”

These works are a continuation of the artists’ subversions of masculinity. The men and boys they are presenting are physically slight, introspective, and probably gay—the opposite of the rugged heterosexual men of action usually placed on pedestals. When they were commissioned to put a sculpture on the Fourth Plinth in London’s Trafalgar Square, in 2012, they created a little boy on a bronze rocking horse—a deliberate contrast to the imperial war heroes on the other three plinths, and Lord Nelson on his column in the center. “It’s important to infuse new dynamics into stuffy institutions,” says Elmgreen. Much to their annoyance, Boris Johnson, who was the mayor of London at the time, told the duo that they weren’t allowed to refer to the Fourth Plinth piece, which was called Powerless Structures, Fig. 101, as an antiwar sculpture. They refused to obey, and when the statue was unveiled, in order to prevent Johnson from introducing it, they asked Joanna Lumley, star of Absolutely Fabulous, to do the honors. “She’s someone who can gather people together instead of upsetting them,” says Elmgreen.

Models for (clockwise from top left) a public art project; Boy With Gun; A Hard Rain’s a Gonna Fall; and Delivery; Coupled Lamp (Eggshell White), 2021; The Touch, 2011.

Photographed by Charlie Gates

While playful, their art is driven by intellectual inquiry: The “Powerless Structures” series, which is ongoing, was inspired by an idea from the philosopher Michel Foucault, that a building or object cannot hold any intrinsic force. They are also fascinated by the way our notion of the home, and what one does there, has changed. “It has become like a vehicle where you do your banking on the toilet and dating in the kitchen—endless tasks that, before, were allocated to other kinds of spaces,” says Elmgreen. In 2009, they represented the Nordic nations at the Venice Biennale, converting the Nordic pavilion into the decadent pad of an art collector who was floating face down in a pool; they also turned the Danish pavilion into another home of collectors, this time a dysfunctional family.

Clockwise from left: L’Addition, 2024; The Drawing, Fig. 3, 2024, a sculpture of a young boy surveying a reproduction of the French artist Thomas Couture’s 1847 painting The Romans in their Decadence; This Is How We Play Together, 2024; This Is How We Play Together, Fig. 3, 2023; The Examiner, Fig. 3, 2024.

Photographed by Charlie Gates

Today, they have more than 30 permanent sculptures and structures scattered around the world, with another due to open in 2026—a large-scale work that will take pride of place in the redesigned sculpture garden at the Hirshhorn in Washington, D.C.

Perhaps the most famous of their permanent works is Prada Marfa, a replica of a Prada store they built in 2005 on Route 90, 37 miles northwest of Marfa, Texas. (It’s actually just outside of a town called Valentine, but Elmgreen & Dragset liked the rhyme in the name Prada Marfa.) The work is at once a critique of consumerism and luxury branding; a comment on the way fashion was encroaching on the art world (Marfa was, at that point, best known as the location of Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation); and a camp rejoinder to macho land artworks like Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty and Michael Heizer’s Double Negative. “At the opening, we had 40 people, most of them local ranchers, coming up to us and saying, ‘Well, we don’t know what this is about, but we certainly think it’s crazy,’ ” remembers Dragset. It was vandalized that very night, with the word “dumb” sprayed on the walls and the stock looted—half a dozen handbags and 14 right-foot shoes, all from that year’s fall collection.

Models for (clockwise from top left) This Is How We Play Together (two figures in gray); Invisible; and a public art project; Laundry, 2024. Photographed by Charlie Gates.

“We thought Prada Marfa would be like the other land art projects that are mythological, but no one really sees them,” adds Elmgreen. Then Instagram happened, and people, including Beyoncé, realized that the store made the ideal backdrop for selfies; it was also featured in The Simpsons. This attention, says Elmgreen, “turned the work into something else. But making artworks is like raising children: You have certain intentions when they’re created, and then they get into the world, take on their own lives, and they’re out of your control and you have to accept it.”

Elmgreen & Dragset’s works have such a sense of prankish capriciousness that it’s easy to imagine them having minds of their own. Sometimes the artists are wryly self-mocking; for instance, their 2010 piece Gay Marriage consists of two urinals connected by their stainless steel tubing. But they can also tackle very serious topics. The duo designed the Memorial to Homosexuals Persecuted Under Nazism, which has stood in Berlin’s Tiergarten since 2008. It’s a gray concrete block that looks as if it has come adrift from Peter Eisenman and Buro Happold’s nearby Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe; through a small aperture in the concrete, you can see a film of same-sex couples kissing. It has been defiled and also criticized—including once by the late historian and Holocaust survivor Israel Gutman, for putting gay people’s persecution by the Nazis on par with that of the Jews. “These fights are definitely not over,” says Elmgreen of the struggles for progressive politics against a general rightward shift. “Women’s right to decide about their own bodies is suddenly on the menu again. In Russia, to be part of an LGBTQ+ organization gets you labeled as a terrorist. We’ve been talking to friends in the art and queer communities about the importance of showing that we stick together across borders.”

Powerless Structures, Fig. 101, 2012.

Photographed by James O Jenkins, Courtesy Commissioned for the Mayor of London’s Fourth Plinth Programme

A sculpture called The Experiment, from 2012, which shows a little boy in white underpants looking in the mirror while wearing lipstick and his mother’s high heels, seems to have anticipated the heated discussions about gender identity of the past decade. The trans perspective is something the duo say they have been energized by. “When you look at young people today,” Elmgreen says, “they don’t operate within the boxes of gay or hetero, or man or woman, in the same way that we had to do in our generation. We can see how hysterically aggressive certain conservative minds get about the so-called woke culture. They feel threatened by a completely new way of shaping identities that I think is extremely hopeful for the world.”

While those culture wars are relentlessly stoked online by characters like Elon Musk, Elmgreen & Dragset shy away from social media. “We are probably some of the slowest Instagrammers in the world; we come up with a post every second week or something,” says Dragset. “We’re a bit embarrassed about entertaining people with too much of the banalities in our everyday life.” Does that mean we shouldn’t expect an Elmgreen & Dragset dance challenge? “We could introduce ourselves as the world’s oldest boy band,” suggests Elmgreen, as a chuckling Dragset does some Backstreet Boys–style arm waving. “I think we have become more and more interested in exhibitions where you have a haptic experience—a bodily, sensory, immersive experience of the art. It’s really important to value the time that we have together in our shared spaces in a physical way. It’s super dangerous if we all end up with a fictional relationship to the world because we only get it through our online feeds.”

A project they are opening this November will certainly prioritize face-to-face interactions: It’s a bar. Dedicated to the German artist Martin Kippenberger, whom Elmgreen describes with some understatement as “a happy drinker,” it seats six, is situated in the remote Khao Yai National Park, in Thailand, and will be open all night, for one night a month, and tended by a man who is currently being trained in Bangkok. An oil painting by Kippenberger, who died in 1997 aged 43, will hang on the wall—a typically Elmgreen & Dragset response to the arguments about the restitution of colonial-era artifacts that have raged throughout the museum world in recent years. “We’re turning that whole discussion on its head,” Elmgreen points out, not by taking artifacts from the Global South and putting them in American or European museums, but “by taking an iconic contemporary art piece and showing it in the countryside of Thailand.”

What will they be drinking? “There will be quite a wide range of cocktails in this bar,” promises Dragset. “It should feel like you’re in a fancy hotel. But I will probably order a Manhattan or a Cosmopolitan—very urban drinks.” And, after five rounds, no doubt dream up some new art from the depths of the Thai jungle.

Photo Assistant: Tommy Francis.