If foreign leaders were hoping that the presidential debate would provide clarity about the future direction of American security policy, they were surely disappointed.

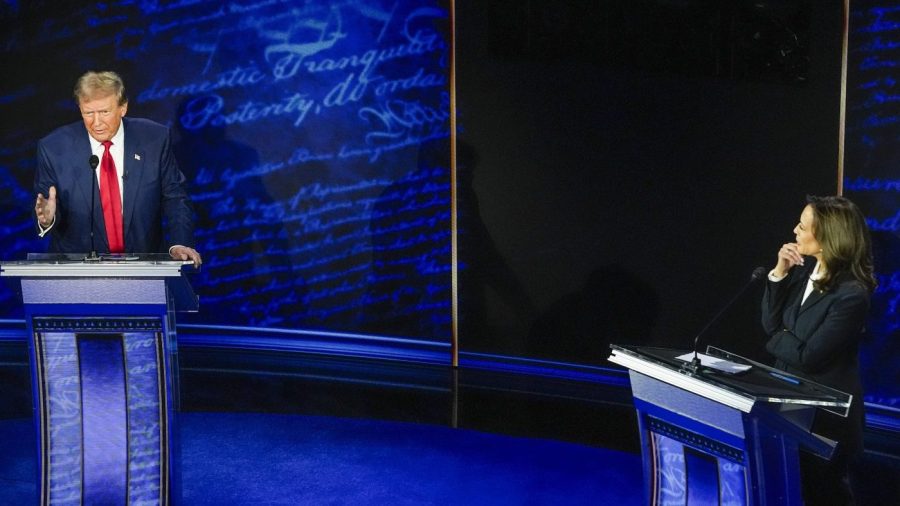

Donald Trump and Kamala Harris exchanged barbs about NATO and allies; about who lost Afghanistan; about who loves Israel more and Iran less; and about which of them is the weaker leader and greater butt of foreign laughter. But neither offered any specifics about foreign and national security policies.

Trump did say that, if necessary, he would employ the military to drive out illegal immigrants from the country, contrary to the 1878 Posse Comitatus Act, which bars federal troops from participating in law enforcement unless expressly authorized by law (as opposed to an executive order). But he said nothing about funding the military to meet external threats from China, Russia, Iran or North Korea.

Trump also asserted that he could resolve both the Ukraine and the Hamas wars almost instantly — indeed, even before he even took office. He did not say exactly how he would do either. He also quoted Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán’s praise for his policies, deftly eliding the fact that Orbán is an outlier within both NATO and especially the European Union.

While Harris outlined some specifics regarding domestic policy, she offered virtually none related to foreign and security policy. She spoke of respect for the military, but was silent about increasing funding for its urgent requirements. She underlined the importance of allies, but didn’t mention any them, other than Ukraine (which is not a formal ally) and Israel (which is), by name.

Harris asserted that she would continue America’s support for Ukraine — in contrast to Trump’s refusal to say the same — but she was silent about acceding to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky’s constant pleas for more weapons, notably F-16 fighter aircraft and long-range ATACMS tactical ballistic missiles. Moreover, she was silent as to whether she would reverse the Biden administration’s prohibition on Kyiv employing American weapons to strike deep into Russian territory.

Harris proclaimed that she would always support Israel’s ability to defend itself, but she said nothing about whether she would put a hold on weapons shipments that she deemed unnecessary for that defense, as Biden did briefly earlier this year. Despite her support for a cease-fire leading to an end to the Israel-Hamas war and the release of hostages, did she spell out how she would make that happen. In fact, she offered no idea as to how Israel and the Palestinians could achieve the ever-elusive two-state solution, other than stating that she supported that outcome.

Neither candidate had anything to say about Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, especially against America’s ally, the Philippines. Neither outlined any steps to diminish the North Korean nuclear threat. Harris avoided any mention of renewing efforts to reach a nuclear agreement with Iran, while Trump asserted that he would reimpose maximum sanctions on Iran, though the sanctions he imposed while president did not stop Tehran’s relentless drive to become a nuclear power.

Neither candidate had a word to say about terminating Houthi attacks on American forces and international shipping in the Red Sea, or about defeating ISIS in Syria, or about the ongoing slaughter in Sudan. Indeed, neither mentioned Africa at all.

Not surprisingly, Trump said nothing about Chinese violations of human rights, or about the importance of human rights generally. But neither did Harris. Nor did either say anything about Chinese theft of American intellectual property, and the dangers China poses as a link in critical American supply chains.

Perhaps, as the race for the White House enters its final stages, America’s allies, partners and adversaries will learn more specifics about each candidate’s plans for the U.S. role on the international stage. They certainly learned very little in the first, and perhaps only, debate between the 2024 presidential nominees.

Dov S. Zakheim is a senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and vice chairman of the board for the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He was undersecretary of Defense (comptroller) and chief financial officer for the Department of Defense from 2001 to 2004 and a deputy undersecretary of Defense from 1985 to 1987.